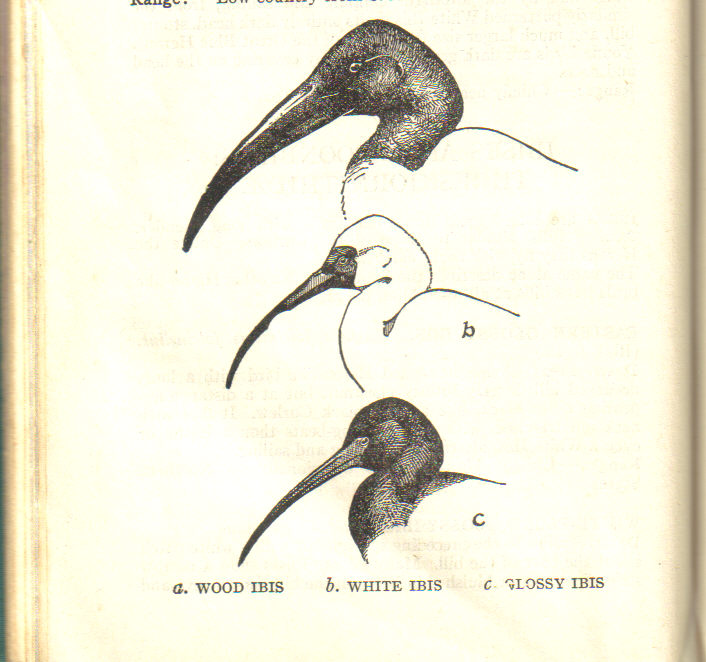

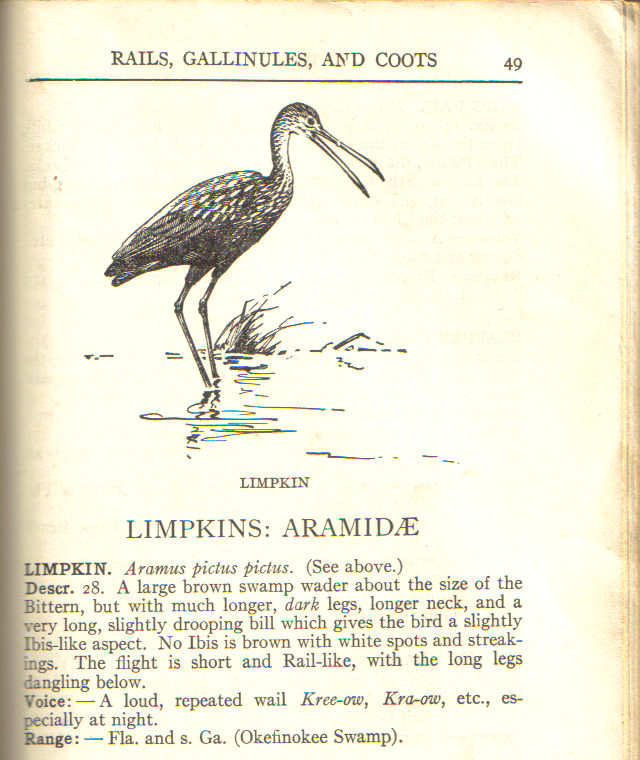

As a child, back in New Jersey, I often took vicarious birding trips to the sub-Tropics. Roger Tory Peterson was my virtual companion (See my review of Birdwatcher: The Life of Roger Tory Peterson). I remember looking through my 1939 Peterson's A Field Guide to the Birds at such exotic southern birds as the Wood Ibis (now properly known as Wood Stork), White Ibis and Limpkin. None of these three were included among Peterson's glossy plates. The former appeared as an ink drawing of its head, comparing it to the White Ibis, which also was not otherwise depicted. (The Reddish Egret, another Deep South specialty, was considered to be so rare that it did not even deserve an image).

A Limpkin was shown calling, and Roger described its cry as "A loud, repeated wail, Kree-ow, Kra-ow , etc., especially at night:"

All these birds had two things in common: they were long-legged waders that I imagined moving through still water among moss-draped trees, and I held out little hope of ever seeing any of them. In those post-Depression days our travel was constrained by the limitations of our family car, a 1937 Ford sedan that, while younger than I, already was showing signs of age. Its exhaust pipe spewed blue smoke, and Dad carried at least a couple of spare rebuilt fuel pumps and extra inner tubes so that he could install replacements when they failed on the road. (I eventually inherited this car and its problems, some aggravated by my own foibles: (Chickie the Cops!)

For our family, Florida was indeed a far-off place, as were destinations anywhere north of Derby, Connecticut, west of Philadelphia or south of Washington, DC, places where we had close relatives. I held hopes of one day seeing a Northern Mockingbird, a Tufted Titmouse, or a Carolina Wren. In my day they were rarely observed in the northern part of New Jersey, but now all three species are common there, . Happily, the Northern Cardinal, which disappeared from its northern range during the early 1900s, (presumably driven out by severe winters) began to repopulate the area around New York City in the mid-1930s and had become quite common in our suburbs by 1945. Similarly, the Tufted Titmouse population was to explode there in the mid-1950s.

Of all the Florida specialties, I was most fascinated with the demure Limpkin, named for its halting gait, and famous for its haunting "mad widow" calls that pierced the night. Hear the cry of the limpkin at this link.

Across the

Everglades: A Canoe Journey of Exploration by Hugh Laussat

Willoughby (1898) "But the worst sound to sleep through is

the cry of the limpkin. When do these birds sleep? or do they ever

sleep ? We have seen them about all day, ..." (Free copy of

this e-book

is available at the link)

Arthur Cleveland Bent, in his classic

Life Histories of North American Birds series wrote (ca 1927):"The

voice of one crying in the wilderness" is the first impression one gets

of this curious bird in the great inland swamps of Florida." He goes on

to quote from a letter he received from T. Gilbert Pearson, who

investigated the status of the limpkin in Florida : "In May, 192l, I

left Leesburg, Florida, in a motor boat, crossed Lake Griffin and

descended the Okiawaha River to its confluence with the St. Johns

River. During this trip of three days, in which a constant lookout was

kept for limpkins, only 11 individuals were seen and another was heard

calling one morning near our camp. Three of the birds were so tame that

it would have been very easy to have shot them from the boat with a .22

rifle. In one case we passed within 40 feet of a limpkin sitting on a

dead limb. The noise of the motor boat did not even cause it to leave

its perch. Natives along the river told me the bird was excellent for

food and some years ago it was not an uncommon custom to shoot 20 or 30

before breakfast... The bird is so easily killed, so highly esteemed as

food, and is found in a State where so little attention is paid to the

enforcement of the bird and game laws, the prospects of its long

survival are not at all encouraging.

If ever I got to Florida, the Limpkin was the bird I most wanted to see. Highly specialized in its diet, the Limpkin subsists almost entirely upon Florida Apple Snails, which it can pluck from their shells in in 20 seconds. Its bill is specialized for the task, as it is compressed laterally like scissors, and its tongue is long, thin and barbed, the perfect tool for extracting the body of the snail.

Nearly extirpated from Florida 100 years ago by hunting and drainage of its habitat, the Limpkin's population has recovered. Of greatest concern is the threat to the native apple snail by competition from introduced Channeled and Island Apple Snails, and by invasive exotic vegetation that replaces the snail's food sources. Although it is currently on the US Fish & Wildlife Service list of Birds of Conservation Concern, the Limpkin is not one of the 200 birds on the American Bird Conservancy and National Audubon Society's United States Watchlist of species in greatest need of immediate conservation efforts.

Mary Lou and I finally got to see our first Limpkin in August, 2002. Our daughter and her husband had just moved to Florida, and we were visiting them from our home in New Mexico. Responsive to our desire to see a Limpkin, they drove us to Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge in west Palm Beach County. We all walked the trails, frantically searching for one, as the skies darkened and thunder boomed in the distance. Under the threat of the approaching thunderstorm, I retreated to the car ahead of them, but they continued their quest. Just as the rain started falling, they ran back to join me, calling excitedly that they had found a Limpkin!

Of course, I thought they were fooling me, and after the storm's initial fury subsided a bit, my son-in-law convinced me that they had indeed seen the bird. Still suspicious, I accompanied him in the heavy rain to a ditch about a hundred yards away from the parking lot. Sure enough, there was a Limpkin, politely enduring the downpour as it awaited my return. That Limpkin was our first Florida life bird. In addition, we saw the endangered Snail Kite, which also is dependent upon Apple Snails as its food source.

These Apple Snail eggs were deposited on a suitable plant stalk at Long Key Natural Area in Davie, Florida:

Limpkins are quite common at Wakadohatchee Wetlands in Delray Beach...

...In Green Cay Wetlands in Boynton Beach...

...and at Shark Valley in Everglades National Park:

In March, 2008 I found this Limpkin, well camouflaged, on a nest in Loxahatchee NWR. Its mate was standing guard, and I did not approach very closely. Males are known to viciously attack any creature that gets too near, including humans:

Now, most of our encounters with Limpkins take place at nearby Chapel Trail Nature Preserve in Pembroke Pines, Florida.. Earlier this year, we heard two Limpkins calling, one on each side of the boardwalk. To my ear, some of the Limpkin's cries include rattling sounds somewhat similar to those of the Sandhill Crane, a related species.

Suddenly, one of the Limpkins flew up to the top of a small tree:

It then surprised us by flying in our general direction:

The Limpkin landed on the boardwalk railing and called again :

When I processed the photo, it provided a clear view of the Limpkin's unusually long and slender tongue:

"Superficially

it looks like a large, heavyset ibis with an erect stance. The neck and

bill are long, the latter laterally-compressed and slightly decurved,

taking a sudden abrupt bend to the right close to the tip. Tip of the

lower mandible is twisted horizontally and sharpened against the tip of

the maxilla, an adaptation for removing snails from their shells. The

tongue reaches the end of the bill and splits into horny filaments at

the tip." www.faunaparaguay.com/aramidae.html

It then flew off in the direction of the second Limpkin:

Our most recent Limpkin sighting was this fly-by, also at Chapel Trail:

Visit http://blog.rosyfinch.com