In an earlier post I discussed the history of the Bald Eagle nest near our South Florida home, the first active nest in our County since the 1960s. At that time we were counting down the days until their eggs hatched.

The eagles in our local nest showed a change in behavior on January 11, which was the 35th day after we determined from our ground observations that the first egg had been deposited. Here is a photo of the male departing the nest after exchanging incubation duties with the female.

The eagles in our local nest showed a change in behavior on January 11, which was the 35th day after we determined from our ground observations that the first egg had been deposited. Here is a photo of the male departing the nest after exchanging incubation duties with the female.

While taking turns incubating the eggs they sat so deeply in the nest that they were nearly hidden behind the rim. On the morning of January 11 the pair suddenly changed posture, sitting up higher, indicating that they were "tenting" a hatchling while continuing to incubate one or more additional eggs. Usually the non-incubating mate would be away for long periods, either foraging or roosting in trees some distance ftom the nest, but now both took an avid interest in the contents of the nest, looking down to tend and feed the new eaglet.

The hatching was publicized in local media and the next weekend many people came to visit the nest area, hoping to see one or more eaglets. Usually they have not been visible from the ground until they were over two weeks old. We visited the nest most of the following mornings, hoping to see them. On January 20 we surmised there were at least two because the adults were carrying food to two different locations in the nest, but the chicks were just out of view.

That afternoon photographer and eagle watcher Liza Morffiz Chevres obtained the first photo of two eaglets during a feeding. Look closely and see that there is one on each side of the parent's beak. Photo is the property of Liza and is used with her permission.

The next day started out with rain, but after the skies cleared Mary Lou and I visited the nest at about 12:15 PM We stayed for an hour. At first the female was on the nest sheltering and tending to the eaglets. The male was not around and the eaglets were not visible.

The male arrived, not carrying prey, and the pair called back and forth.

He briefly roosted on the horizontal perch above the nest and then flew in a circle around the nest.

The male returned to the perch and continued resting there until we departed.

In the meantime, the female began tearing at the large white bird that had been on the nest since the day before.

After eating quite a bit she started feeding the eaglets.

The eaglets were hidden in the rear left portion of the nest, where the rim is also higher, so they remained out of view......until we finally caught sight of one.

The nest is full of feathers from prey, mostly White Ibises and Cattle Egrets. The wind blows the feathers and gives the impression that we are seeing the movement of an eaglet. On January 23 I took almost 300 photos of the eagles feeding their young, but in only one frame did I find this poor image of one of the eaglets:

Today is the tenth anniversary of my father's death at the age of 95. Yesterday, thinking about this drove me to reflect upon the shrinking wild areas near my childhood home in Rutherford, New Jersey. When I was quite small Dad would often take me for "nature walks," as we called them. I eagerly anticipated those Saturday mornings and was disappointed when it rained or when other obligations got in the way.

So I fired up Google Earth to see if anything was left of those places. Two in particular were small pockets of wetland that sometimes held water all summer and even attracted nesting Mallards. Using Google Street View I "walked" from our home on Springfield Avenue west on Cooper Place, down the hill on what was a cobblestone road but now is paved with asphalt. Most of the frame homes still looked familiar.

I "crossed" busy Jackson Avenue, and made a dogleg turn to the left and then west again on Hastings Avenue. No longer a dirt road that narrowed into a winding path, it was neatly paved, lined with apartments and ended in a cul-de sac, ringed with upscale living units that overlooked the Passaic River. The river was now contained behind bulkheads and its sharp edges neatly landscaped.

Dreams are weird. Last night I dreamed I was a child walking that path, all the way through "Charlie's Woods," past the pond with the "warbler tree," to the banks of the river. I was with another kid, my cousin Corky, I think. Yet I somehow was also in the present, as I knew that Dad and Corky were long gone and that I lived in Florida. I awoke thinking about blogs I wrote about those days. The first is an excerpt written eight years ago, and the second on the third anniversary of Dad's death.

* * * * *

On Saturday mornings, Dad would often take me on walks over to the west side of Jackson Avenue, a wooded strip a quarter to a half mile wide that extended to the Passaic River. In the winter, we followed the tracks of rabbits and mice in the snow. Once we saw the dramatic record of an encounter between a rabbit and a large bird of prey, probably an owl. The rabbit’s tracks ended suddenly in a disturbed area that showed the imprint of wing feathers and a little blood. At Dad’s funeral, I talked about how special those memories were to me. Maybe he knew, too, but I never told him directly.

On Saturday mornings, Dad would often take me on walks over to the west side of Jackson Avenue, a wooded strip a quarter to a half mile wide that extended to the Passaic River. In the winter, we followed the tracks of rabbits and mice in the snow. Once we saw the dramatic record of an encounter between a rabbit and a large bird of prey, probably an owl. The rabbit’s tracks ended suddenly in a disturbed area that showed the imprint of wing feathers and a little blood. At Dad’s funeral, I talked about how special those memories were to me. Maybe he knew, too, but I never told him directly.

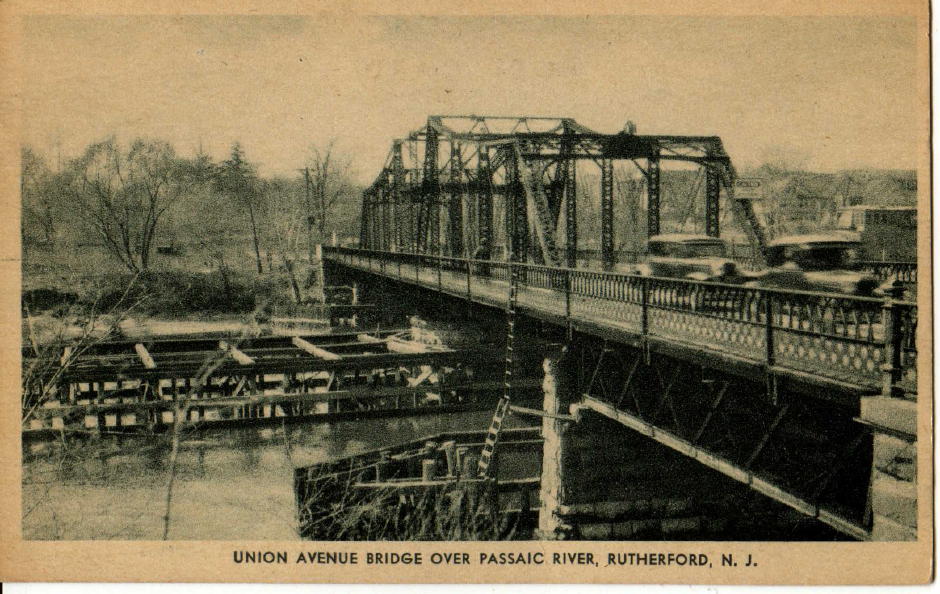

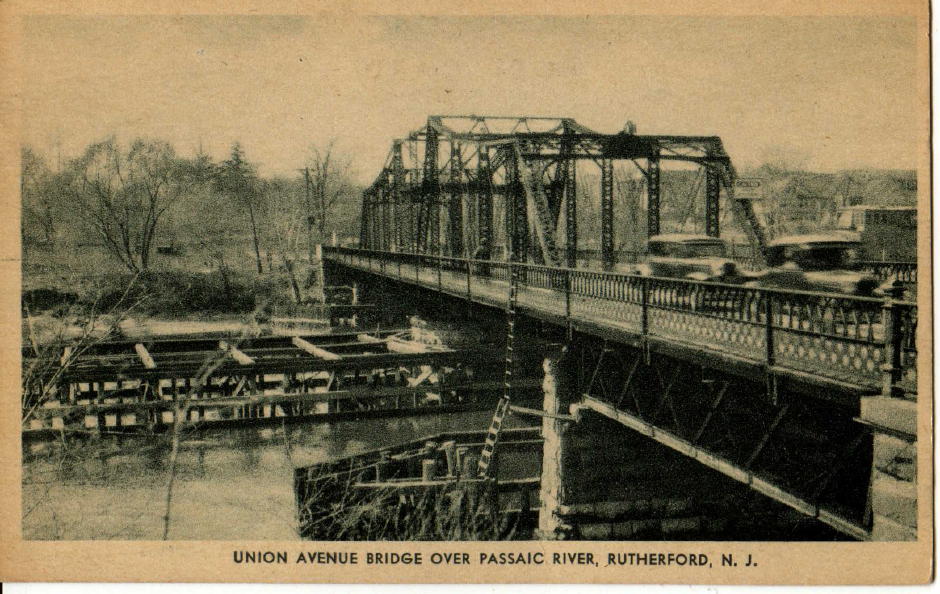

New Jersey in springtime was one of the greatest places to see beautiful and colorful migrant birds such as warblers, orioles and tanagers. Even before their leaves fully opened, trees would be alive with warblers of many species. Rutherford now is but a ghost of the birding paradise my friends and I trudged in the 1940s and 50s. My logs refer to the extensive sand dunes along the Passaic River, where cuckoos nested and shrikes impaled insects on thorny twigs. Barn Swallows nested on the abutments of the Union Avenue Bridge (Postcard view to the right). Two spots were especially famous for their variety of birding habitats: “Charlie’s Woods” and “Strinchuck’s Pond.” All are now gone, converted into homes and apartments.

tanagers. Even before their leaves fully opened, trees would be alive with warblers of many species. Rutherford now is but a ghost of the birding paradise my friends and I trudged in the 1940s and 50s. My logs refer to the extensive sand dunes along the Passaic River, where cuckoos nested and shrikes impaled insects on thorny twigs. Barn Swallows nested on the abutments of the Union Avenue Bridge (Postcard view to the right). Two spots were especially famous for their variety of birding habitats: “Charlie’s Woods” and “Strinchuck’s Pond.” All are now gone, converted into homes and apartments.

One day my cousin Corky and I caught a batch of “frogs” in Strinchuck’s Pond. We killed and skinned them and fried their legs on a piece of rusty tin with a little bacon. They tasted just fine. Yet they may actually not have been frogs at all, but toads! One spring we caught hundreds of garter snakes. We stuffed them into our pockets and into a bucket we found, intending to release all of them in my backyard. I forgot about the ones in my pockets and they turned up in the washing machine, to Mom’s horror.

We were attuned to the smells of the woods as the seasons changed. Skunk Cabbage was easy to detect in early spring. As the earth warmed we could smell the garter snakes as they came out of hibernation and began mating. Around mid-August there was a particular type of small red ant that gave off a kind of perfume as the winged adults emerged. They had a bitter-sweet taste (the front 2/3 were bitter and the rear 1/3 quite sweet). Yes, we ate some crazy things, but these ants actually smelled good enough to eat, so we tried.

Several of my childhood friends shared my interest in birds. We grew up together, some from kindergarten right through high school. We gradually came to realize that the larger world did not look as kindly upon people who walked around with binoculars. As we advanced in age and wisdom, we found it prudent not to be labeled as “bird watchers.” There were fewer opportunities for group birding. Solitary bird watching did not appeal to me. Competing and collaborating with others to spot and identify bird species is energizing. Seeing new places was not as much fun alone as it was when there was someone to share the experience. I resolved that when I married, it would be to a birdwatcher.

I became a sneaky birder. No one around me knew how happy I was to finally see my first mockingbird (more recent photo above) when I attended a wedding in Maryland. My birding activities ebbed to an all-time low through college and medical school, but picked up after I went into private practice in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Dr. Adrian Sabety, a local surgeon colleague, was an expert birder. We made time to get out to bird locally, if only briefly. We often visited the nearby Watchung Mountains, where hawks congregated during migration. It seemed only a few people even knew about it, but it was to become quite a famous hawk-watching spot.

* * * * *

My fondest memories of childhood were not those of solitary pursuits. Not having someone there to share an otherwise awesome event seems to take the edge off the experience. Maybe it’s because I simply want to say, “Hey, look at that!” and feel the satisfaction of having another appreciate and later reiterate the experience. Frequently, it works the other way. So many times I might have missed what another pointed out or interpreted.

My fondest memories of childhood were not those of solitary pursuits. Not having someone there to share an otherwise awesome event seems to take the edge off the experience. Maybe it’s because I simply want to say, “Hey, look at that!” and feel the satisfaction of having another appreciate and later reiterate the experience. Frequently, it works the other way. So many times I might have missed what another pointed out or interpreted.

I feel some sadness when I see parents showering their children with expensive gifts and elaborate parties. How often are the kids more fascinated with the packing crate than the contents? Yes, that Christmas when I received the full-sized balloon-tired two-wheeler persists in my memory, but I smile and relax when I think of those woodland walks with my father. The day we encountered a young Great Blue Heron who could not become airborne because it was trapped among dense trees along the Passaic River—how Dad covered its head and mean-looking beak with his jacket so we could carry it out into an open field—the thrill of seeing the bird slowly rise on untried wings…

One Spring I attended a week-long medical refresher course at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park, Colorado. I invited my parents to join us, and they flew to Dallas. Mary Lou and I and our four children set out with them in our 1972 Oldsmobile Custom Cruiser station wagon. Despite the demands of the curriculum, we found time to walk the trails and see deer, beavers, American Dippers and a family of Blue Grouse (now known as Dusky Grouse).

We had followed a direct route to Colorado, but after the conference I took leave for a few days to permit a more leisurely trip back to Texas. On the return leg, we spent two nights at Kachina Lodge in Taos, New Mexico.

We had followed a direct route to Colorado, but after the conference I took leave for a few days to permit a more leisurely trip back to Texas. On the return leg, we spent two nights at Kachina Lodge in Taos, New Mexico.

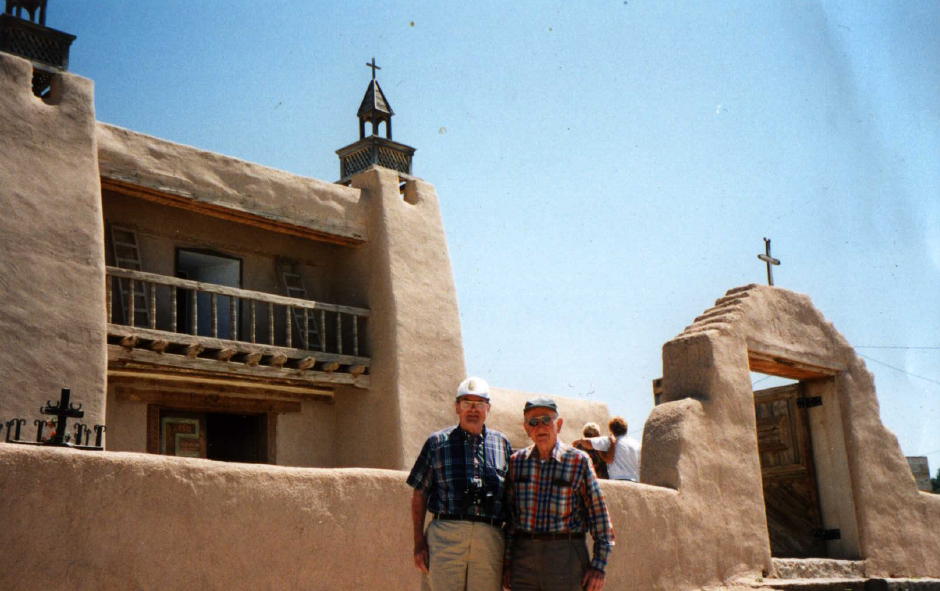

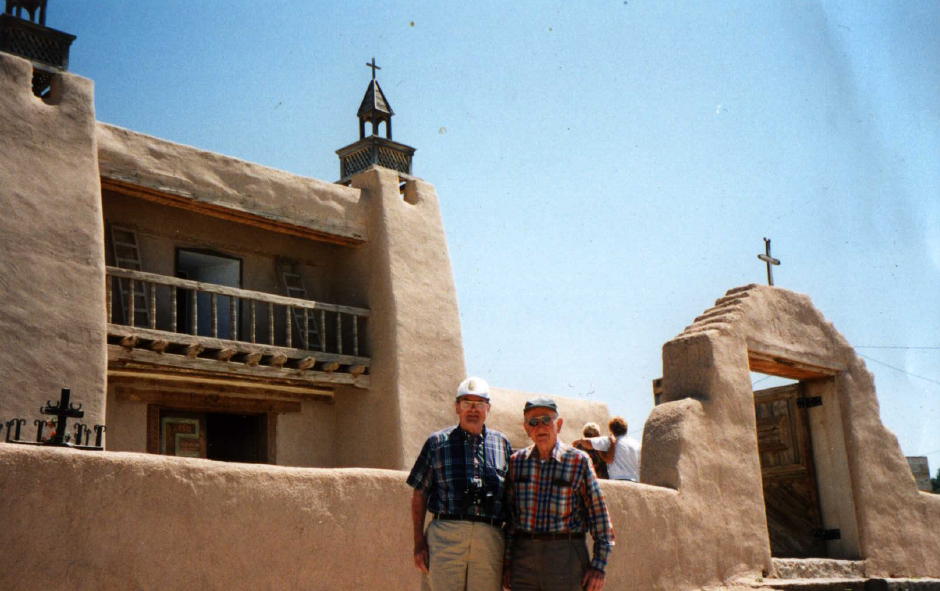

The first night we watched Pueblo Indian dances, and the next morning we attended Sunday Mass at San Francisco de Asis in Ranchos de Taos. This adobe church, completed in 1815, is said to be the most photographed church in America. (Dad loved the old churches of New Mexico. The photo shows him, on the right, with his brother, Father Dan, on the High Road to Taos, visiting the church at Truchas/Las Trampas).

The ceremony was entirely in Spanish. It happened to be Father’s Day. The priest invited all fathers to join him on the altar to recite the Lord’s Prayer. Dad and I walked up and joined the congregation in prayer. I knew some Spanish, but Dad knew none. That did not dissuade him. He put his hand on my shoulder and launched into the Latin version of the prayer. While everyone else was saying “Padre nuestro que estás en los cielos, santificado sea tu nombre…” Dad was confidently announcing “Pater noster qui es in coelis, sanctificetur nomen tuum.” The Romance cadences were so similar that no one seemed to notice. That Father’s Day and all others afterwards held special significance for me.

During my working years I enjoyed beating the traffic and getting to the office early. I was able to close my office door and organize my day in peace and quiet before my co-workers appeared. When I retired from active duty I resolved never to sleep late. Therefore, when we moved to the mountains of New Mexico I set the alarm on my watch for 7:30 AM to nudge me awake just in case, but I rarely needed it. Dawn came quick and bright as the sun emerged in a blue sky above the ridge to the east.

So it happened that on Sundays, 7:30 AM Mountain Time was an ideal time for me to call my father, back home in New Jersey. By then he had returned home from early Mass and had finished his breakfast, and was in the middle of his morning papers. The chirp of my watch alarm was a gentle reminder, and rarely did I miss placing the call. If I happened to be a little late, he would ask about the reason for the delay. At Dad’s funeral, his younger brothers told me how important those calls were to him. Unbeknown to me, he arranged his Sunday morning schedule to accommodate my call.

We talked about nothing in particular, though we often filled the greater part of an hour with banter. Embedded among discussions of the weather, politics and sports were those “I wish you could have seen…” and “Remember when we…” moments that swept us back to those earlier days.

I last called Dad only a few days before he died. He spoke of how wonderful it was to have a hospital room with a view.

Now in the Eastern Time Zone, my wristwatch still chirps at 7:30. Though two hours earlier in real time, the sun already dapples on the surface of our lake. And I whisper a Pater Noster in remembrance.

Our local pair of Bald Eagles are expecting a new arrival on or about January 11. We have monitored this nest, located about 2 miles from our home, since it was discovered in the spring of 2008. In December, 2007 we saw a pair of eagles copulating on the roof of a home across our lake. The nest was finally discovered in March, 2009.

Adult eagles, presumably members of this pair, were sometimes seen singly, wandering in our general area during this past summer, but both appeared together at the nest in mid-September. Within a few weeks they began adding sticks to the nest, which is now very large-- at least 6 feet high and just as deep.

They sometimes did not agree as to the exact placement of the building materials. Here the female tried to move a stick while the male was sitting on it, and he reached around as if to stop her.

The female won the tug of war.

With the nest enlarged and renovated to the pairs' satisfaction, the male positioned a dried palm frond, to become part of the softer lining.

They often took a break from their duties and roosted on the snags of dead Melaleucas nearby. This is the male.

They often took a break from their duties and roosted on the snags of dead Melaleucas nearby. This is the male.

The female is noticeably larger and heavier .

They sometimes try to rest upon rather precarious twigs.

As egg-laying time approached, they often spent time perching together. This time they stopped traffic by selecting a dead tree almost over a busy roadway.

Incubation began promptly as soon as the first egg was laid. One or two more eggs may also have been deposited over the next 3 to 5 days, but presently there is no way of knowing. Without a nest camera we must depend up on the behavior of the female. In the days before egg laying she spent much time sitting on the nest, but interrupted this by flying away and foraging. On the morning of December 7 she settled deep in the nest and just remained there.

Both adults took turns incubating during the day, usually about every two hours or so, but the female seemed to spend all night on the nest. The sitting adult often called out before the other approached. Here the male kept calling until the female settled in, then he took flight.

He continued calling from a nearby perch.

On January 5 she got up to stretch her wings and rearrange the egg(s).

Over the past six breeding seasons, we have observed 11 eaglets, of which 9 are known to have successfully fledged. Interestingly, as we watched the above behavior, an immature eagle flew in front of our nest. I was able to snap a couple of poor photos. Other observers later photographed it roosting near the nest. It is very likely the eaglet that was produced last year.

Over the past six breeding seasons, we have observed 11 eaglets, of which 9 are known to have successfully fledged. Interestingly, as we watched the above behavior, an immature eagle flew in front of our nest. I was able to snap a couple of poor photos. Other observers later photographed it roosting near the nest. It is very likely the eaglet that was produced last year.

Ground observers will be watching closely this weekend for signs that the egg has hatched. This is usually indicated by a change in the incubation posture-- the adult will sit higher in the nest, "tenting" the chick with her wings while also continuing to incubate any additional eggs. Both parents will usually spend some time looking down into the nest like proud parents. Within two to four days we will witness feeding, and after about 7 to 10 more days we hope to see a little puff of white down appear over the edge of the nest.

For more photos and information, including the announcement of hatching, visit our "Bald Eagles of Broward County FORUM" at this link.