This was much easier said than done. We collected the remains from dinner and afterwards picked away at the bones, ending up with a greasy mess. Neck vertebrae were a hopeless tangle of ligaments and windpipe. Cartilage stuck to the drumsticks. The wishbone had been broken (for good luck).

I came up with a better idea, to slow-cook another chicken in a Crock Pot. We could make soup with the stock and expect the softened meat to fall off the bones. This worked fairly well. We cleaned the bones, washed them with detergent and let them dry out.

The difficult job was putting the bones back in proper order, but we accomplished this and secured the joints with globs of clear silicone adhesive. Mounted on a stand I made from clothes hanger wire, it was quite an impressive skeleton, despite the missing head and feet. The restored neck bones curved up nicely. Our daughter named the chicken "Ezekiel" of biblical dry bones fame. She didn't win the science fair, but her project got lots of attention. Ezekiel's skeleton survived for several more years as an adornment in her bedroom, until it broke apart.

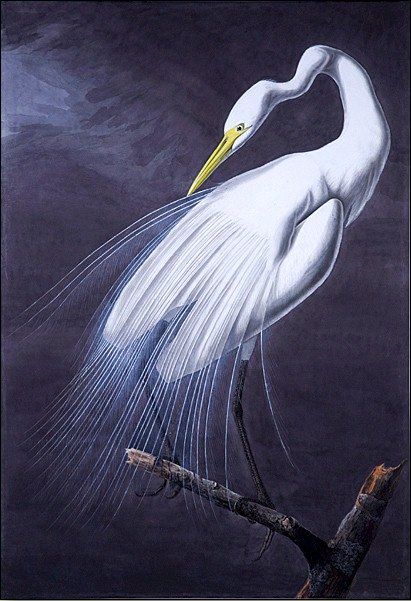

Given this experience, if I had worked on God's assembly line I would have provided the herons with a much more graceful neck. I don't know how you feel about this, but there must have been a mistake in its creation. I want an egret or heron's neck to form graceful curves, such as depicted by John James Audubon.

Instead, I see an ugly kink that interrupts the pleasant "S" curve in this Great Egret's neck. Why would it have a 90 degree zig-zag that constricts its spinal cord, or maybe even interferes with swallowing a big fish? To Audubon's credit, his paintings are anatomically correct, as the kink is obscured by careful positioning of the birds' necks.

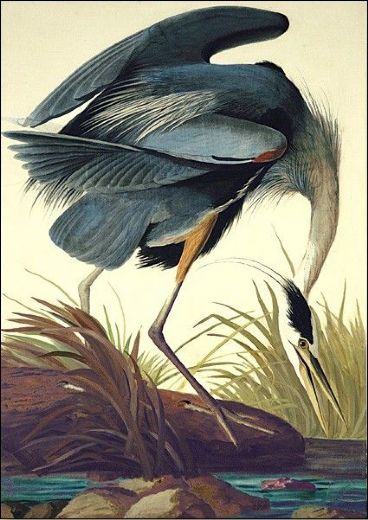

There it is again, in this Great Blue Heron!

My goodness, the Anhinga's neck takes a funny turn as well!

In nature, every structure serves a purpose. Sometimes the purpose is not very evident. It may be a remnant of some useful ancient mutation, important to survival during evolution of a species.

Is the kink in a heron's neck similar to the human appendix, which seems unnecessary and superfluous, leaving us with a reminder, evidence of an evolutionary "blind alley" (pun intended)? Although seemingly of little use, the human appendix does serve an important immunologic function from early fetal development into young adulthood.

Does that kink in the heron's neck possibly have some reason for being?

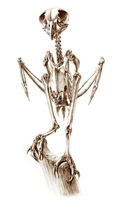

For the answer I turned to a book with an odd title: The Unfeathered Bird, by Katrina van Grouw (Princeton University Press). I leafed through it, expecting this book to be about birds in various stages of undress. Instead I found a dazzling array of drawings of the bony parts of many bird species. There are drawings of full skeletons as well as single bones or sets of vertebrae, ribs or limbs. Sometimes the muscular attachments or flight feathers are included, as are skulls, beaks and feet. The illustrations are not diagrams or outlines, but finely detailed and artfully executed.

The culmination of a twenty-five year project, The Unfeathered Bird is not simply about bones. It represents deep research into not only comparative anatomy, but also physiology, bird behavior, body mechanics, taxonomy, paleontology and evolutionary biology.

The book consists of two major sections, Generic and Specific. The former, in about thirty pages, explores those features common to most birds and illustrates adaptive variances. As different as birds might appear, their skeletal and other internal features bear a certain sameness.

The concise text is not only extremely informative, but also makes for very enjoyable reading. A bird's trunk is a rigid and light weight airframe, which requires great mobility of the head and neck to permit preening and feeding. The hind limbs project underneath rather than outward as in reptiles, and must be strong to compensate for the lack of forelegs. Feet are adapted for specialized tasks such as running, grasping prey or food, climbing, digging, and swimming. Birds usually have four toes, but there may be only two (as in Ostriches), three (only two facing forward) in kingfishers, or even five in some domestic fowl. The wings generally contain little muscle, relying on those of the breast, which provide the strong downstroke so essential for flight.

The Specific section addresses six major groups of birds that share similar anatomical characteristics, but they are not arranged in strict taxonomic order.

For example, the chapter on "Accipiteres" includes hook-billed birds that eat the carcasses of other animals: vultures, birds of prey and owls. This approach provides the opportunity to explore particular adaptations.

Vultures, facing an uncertain and sometimes scarce food supply, cannot waste energy. Their wings are specialized for soaring, which conserves energy and allows them to cover great distances.

Diurnal raptors often have surprisingly small bodies under their bulky plumage and long tails. Rather than relying upon long distance flight and endurance, they often spend much time roosting or sailing and making high-speed forays after prey. Their broad breastbones and wide wishbones accommodate short, strong bursts of flight.

Owls have comparatively low body weight that puts less load on their wings and permits nimble and stable flight even at low speeds. Owl bones are not the only focus of this section-- indeed the following reinforces my point that this is not a "book about bones." In easy prose the author discusses the wide gape of owls that permits them to swallow whole prey, and expanding the topic, mentions that owls regurgitate the indigestible parts of prey items as pellets:

"Owl pellets are large enough to be studied with ease in the classroom or laboratory, giving a good indication of exactly what the bird ate for its last meal. So strongly associated are pellets with owls that many people don't realize that they are not exclusive to them-- virtually all meat-eating birds produce pellets, even small insectivorous species."

She reminded me of an American Kestrel I photographed (badly) as it appeared to be retching almost convulsively.

Suddenly a pellet appeared in its mouth and dropped to the ground before I could snap another picture.

Among the other groups are the "Picae," from parrots and kingfishers to woodpeckers and hummingbirds, all with sharp-edged bills and short legs, among other shared characteristics, "...anything that seemed too large or too unusual for the perching birds."

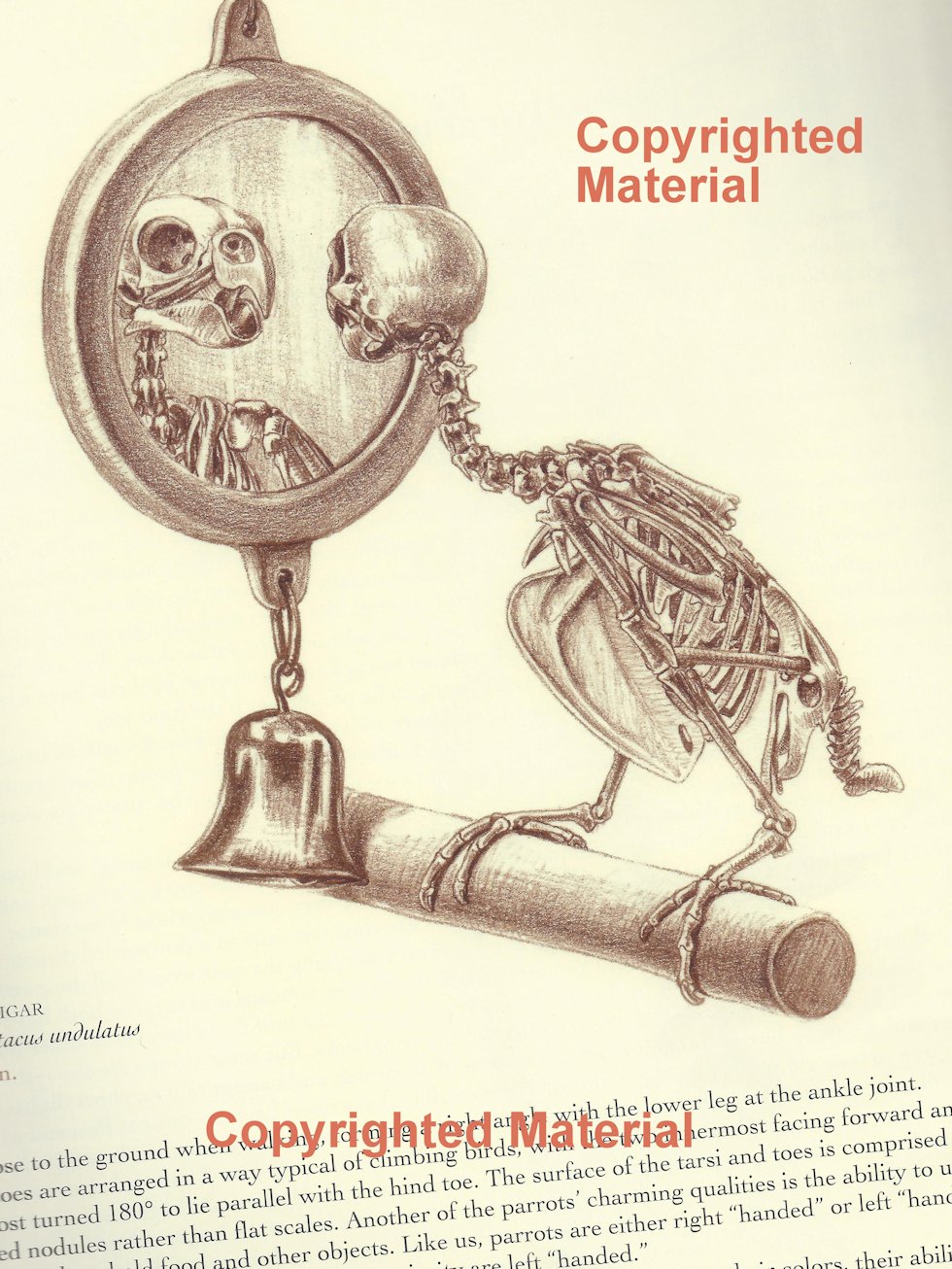

Humorous illustrations in this chapter include a macaw with its skin removed, chewing on a pencil, and a Budgerigar skeleton looking at itself in a mirror!

Typically, Katrina van Grouw reveals her conservation concerns, here by calling attention to the decimation of some parrot species by the pet trade. Despite their engaging and gregarious personalities, captive parrots lead a dismal life: "More often than not the result is a pitifully bored and frustrated animal eking out a long and unhappy existence in the corner of an empty room."

Waterfowl such as ducks, geese, penguins, loons and grebes are grouped as "Anseres;" domestic chickens, gamebirds, ostriches and bustards are among the "Gallinae," while "Passeres" encompasses perching birds as well as pigeons, nightjars and swifts.

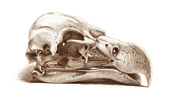

In view of my concern about the "kink" in herons' necks, I jumped to the chapter entitled "Grallae," as it includes herons in addition to flamingos, storks, ibises, spoonbills, cranes and rails. This succinct statement, typical of so many passages in The Unfeathered Bird, provided the needed clarification:

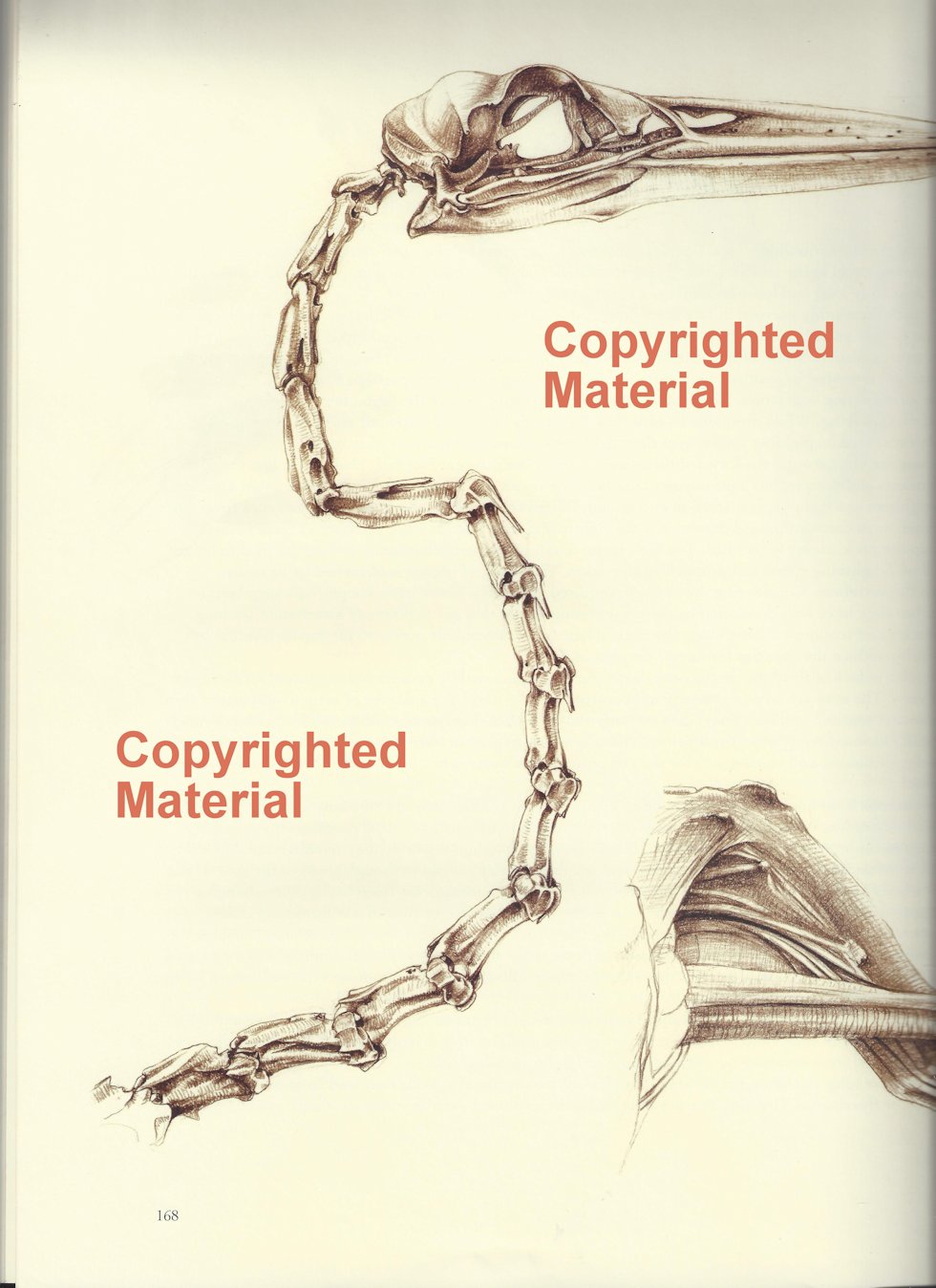

"Herons are built around the forward thrusting action of their dagger-like bill. Their neck, like the neck of cormorants and darters, has a permanent kink in it, the result of a single elongated vertebra that is attached to its neighbors at a right angle instead of end to end. In herons, however, this is the sixth vertebra from the skull, whereas in cormorants and darters it is the eighth, meaning that the kink in a heron's neck is slightly higher up the neck, closer to the head. The kink forms a sort of hinge mechanism, enabling the bird to lunge forward at lightning speed and astonishing precision."

The "errant" horizontal vertebra is beautifully shown in this drawing of the similar Grey Heron's neck bones:

This book is large and heavy, measuring 10 x 12 inches. It is a work of art to be enjoyed at the coffee table but also to serve as a unique and valuable reference.

The Unfeathered Bird

Katrina van Grouw

Cloth | 2013 | $49.95 / £34.95 | ISBN: 9780691151342

304 pp. | 10 x 12 | 385 duotones/color illus.

304 pp. | 10 x 12 | 385 duotones/color illus.

eBook | ISBN: 9781400844890 |  Where to buy this ebook

Where to buy this ebook

Katrina van Grouw's Home Page Where to buy this ebook

Where to buy this ebook

Small images linked from Princeton University Press

pretty neat illustrations.

ReplyDeleteKen, I enjoyed this book as much as you obviously did. In fact I think it a fabulous and unique book. Your review was very original and thought provoking and illustrated with fine pictures, just like the book. Audubon's drawings may never be bettered in my opinion and you can see from where Katrina drew some of her inspiration.

ReplyDeleteGreat book review..and how great to find the answer to your "life's mystery" questions. You have the mind of a researcher and I'm grateful that you shared your discovery so clearly and beautifully.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting - I enjoyed your word and photo illustrations!

ReplyDeleteLovely post, great photos and "drawings"!

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed reading your critique. And the fact that you accomplished the skeleton project astounds me!!

ReplyDeleteNeat post! I enjoyed the drawing and the photos. Have a happy day!

ReplyDeleteGreat shots and interesting info Ken. I would love to have seen your daughter's reconstructed chicken!

ReplyDeleteInteresting info. A few years ago we used sterilized owl pellets with our fourth grade students. It was fascinating seeing what we found inside.

ReplyDeleteWhat an interesting review. I think I'll put this book on my wish list!

ReplyDeleteFascinating! Thank you!

ReplyDelete