Shades of gray can be beautiful, but also confusing to a young birder.

Back in New Jersey on August 21, 1949 I saw my first Loggerhead Shrike. It was my Life Bird #119. Actually, a few days earlier I had found grasshoppers impaled on the spikes of a barbed wire fence in the Passaic River bottomlands a short walk from my home in Rutherford.

I had read about how the "Butcher Bird," whose "weak feet" lacked the talons of raptors, must stabilize its victims in this manner to permit them to be torn apart with its hooked beak. Hoping one day to see mice and small birds in a shrike's larder, I did not expect lowly insects. I searched for the shrike to no avail until three days later, when I caught sight of my "lifer."

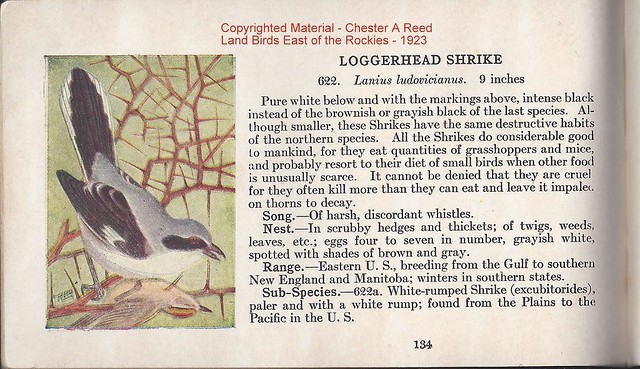

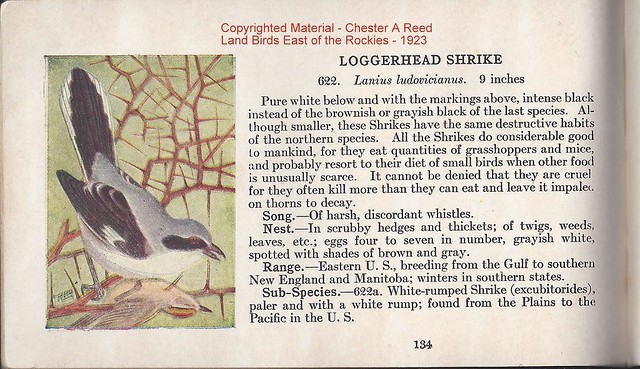

I did not know exactly what to call the bird, as nomenclature was confusing. My tattered little pocket Chester A Reed guide (published in 1923) called it a "Loggerhead Shrike." In those days birds were considered to be either "good" or "bad," but in Reed's opinion the shrike seems to straddle the line.

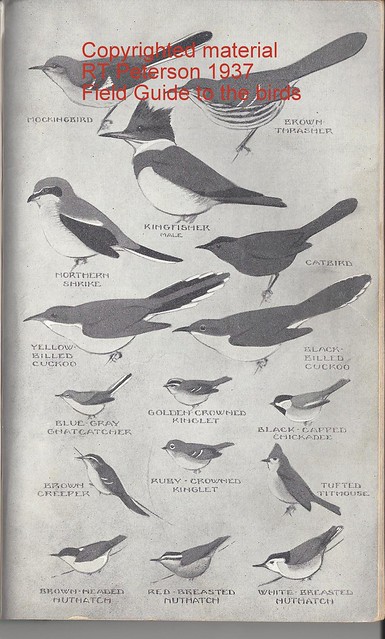

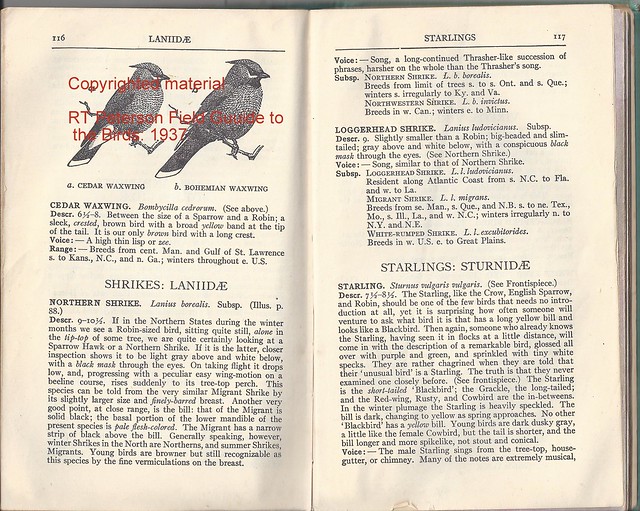

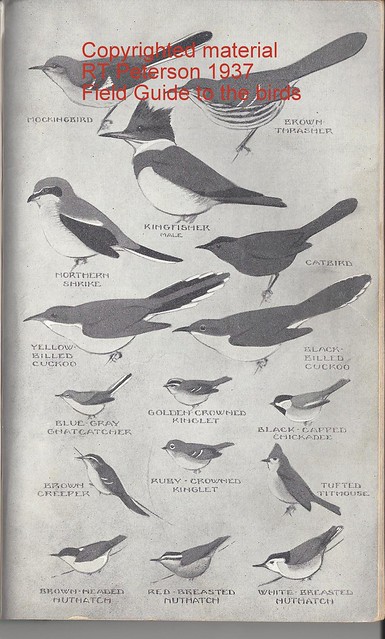

More up-to-date, my 1937 Peterson Field Guide to the Birds only illustrated the larger (and even less common) Northern Shrike:

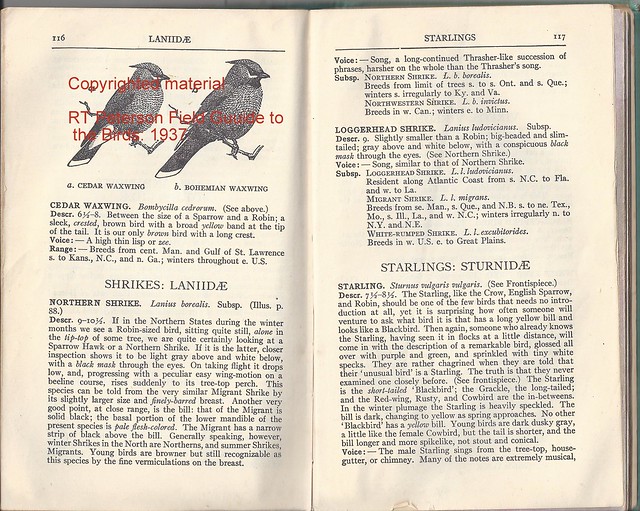

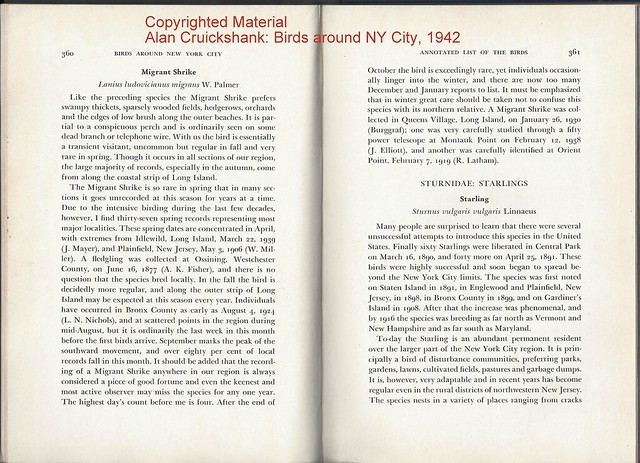

The text was not very illuminating, as it gave short shrift to the Loggerhead or Migrant Shrike as it was called:

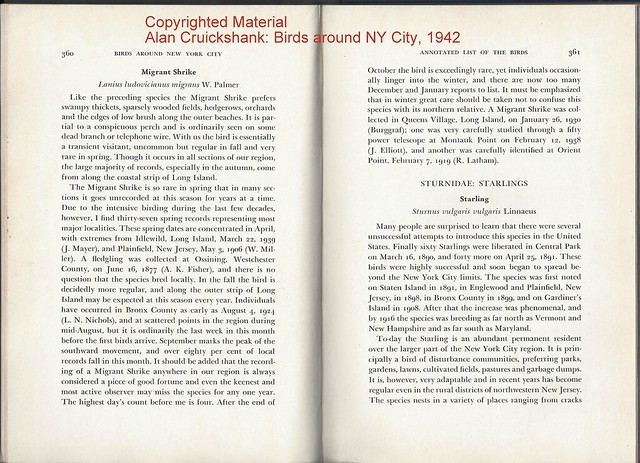

My "go to" reference for information about distribution and abundance was Allan Cruickshank's "Birds Around New York City (1942). I was elated that I had seen a relatively rare bird. Cruickshank reverted to calling it a "Migrant Shrike."

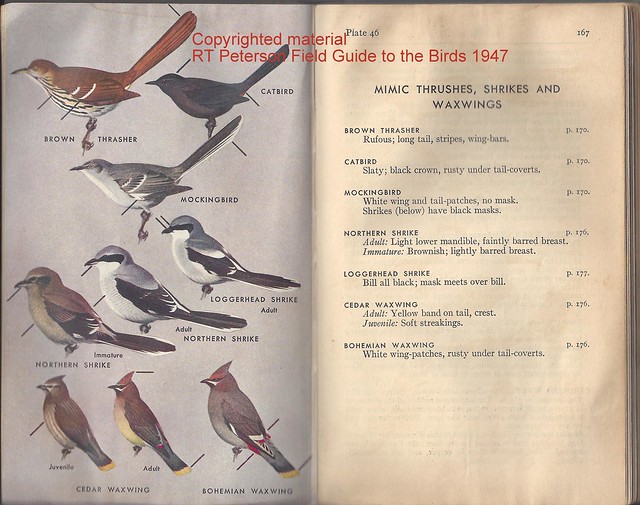

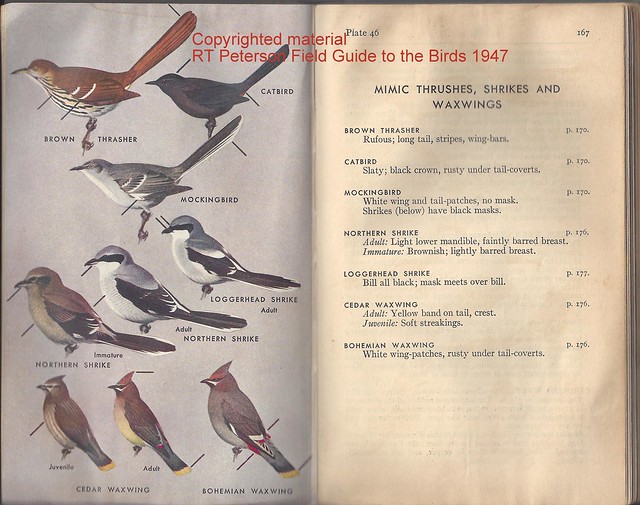

Only later, during the year of my first sighting, did Peterson's 1947 Guide appear, with the Loggerhead Shrike in all its glory.

During the 20 years following my sighting, the Loggerhead Shrike became more common in New Jersey, especially in the southern reaches of the state. However their numbers decreased and they once again became quite rare towards the end of the 20th Century up to the present. Ingestion of pesticides in insect prey is strongly suspected as the cause of their drastic decline. In south Florida, now my home, they are quite common breeders and winter visitors.

Cold light brings out the blue:

Their prey is varied, but mostly insects. I think this huge grub is a horsefly larva.

Except during the breeding seasons, Loggerhead Shrikes tend to be solitary. They often select the highest perch...

...and may be challenged by grackles...

...mockingbirds...

...and Blue Jays. In this case, the shrike retreated, possibly to simply avoid the company of others.

Yet, many time I have seen a shrike sit peacefully with a variety of other species, such as this American Kestrel...

...or a Northern Flicker.

One of my more remarkable shrike images includes two shrikes with a Belted Kingfisher and a kestrel, in late November.

In June the shrikes are courting.

I usually find it difficult to get any closer than 30-40 feet from a Loggerhead Shrike, but this fledgling was an exception.

The shrikes like to hunt for lizards on our back patio, so I can get some close views through the glass doors.

Parents watched this youngster as it unsuccessfully pursued a Brown Anole. They did not intervene, perhaps to teach their fledgling the importance of stealth and persistence.

I will be away from Internet and cell phone service for much of these two weeks and prepared several posts in advance, but plan to get back with a "live" report as soon as possible.

Picoides is a genus of woodpeckers resident primarily in North America. Their plumage is characteristically black and white or brown and white. Males often have a red badge on the back of their heads. In the eastern US the most common species are the Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers. While they differ in size and bill length, their plumages are strikingly similar.

The Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) is the smaller of the two, measuring 6 3/4 inches (17 cm).

They are active little birds, often leaping from branch to branch as they forage by hammering into the bark.

The female Downy Woodpecker lacks the red patch on her head.

Downy Woodpeckers typically show a few black markings on their outer tail feathers. I have seen some in New Mexico, such as this one, with clear outer tail feathers.

This melanistic female Downy Woodpecker appeared in one of my south Florida neighbor's yard, drumming on a dead branch of a tree. Its head was almost entirely black and its back was heavily barred. I could find no other such a specimen when I searched the Internet for photos. Her mate had typical standard plumage.

The bill of the larger Hairy Woodpecker (Picoides villosus) is about as long as its head. In fact, I often say that if you could drive its bill into his head it would stick out slightly in the back (not too appealing!).

The Hairy Woodpecker measures 9 1/4 inches (24 cm).

Hairy Woodpeckers nearly always have pure white outer tail feathers. I remember this by saying "The Hairy Hain't got no tail bars."

Hairy Woodpecker in flight:

Pair of Hairy Woodpeckers. It is often said that they do not have the "cute" look of the smaller Downy.

This is the related Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Picoides scalaris) of the arid southwest, photographed in New Mexico.

This is my only photo of a Nuttall's Woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii), a poor image of one in California, retained for documentation:

I have not yet gotten photos of these other members of the Picoides genus which are found in the USA:

Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis)

American Three-toed Woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis)

Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus)

White-headed Woodpecker (Picoides albolarvatus)

Arizona Woodpecker (Picoides arizonae)

I will be away from Internet and cell phone service for much of these two weeks and prepared several posts in advance, but plan to get back with a "live" report as soon as possible.

In an earlier post I discussed the interesting geology of the prairies of northeastern Illinois and how pollen studies at Nelson Lake/Dick Young Forest Preserve revealed a great deal about the evolution of the grasslands. Following the retreat of the glaciers 16,000 years ago, lush evergreens were succeeded by hardwood forests which then retreated as the climate warmed and rainfall diminished. The tallgrass prairies that greeted the first European settlers had reached their full extent only 3,500 years before Europeans arrived. During the past century the hand of man has rendered the prairies mostly extinct, their lush soil nourishing corn and soybean crops.

Nelson Lake and the surrounding woodlands, prairies and marshland are actively managed by the Kane County Forest Preserve District. A program of controlled burns, removal of exotic vegetation and planting of native trees and shrubs is returning this 1,285 acre (2 square miles) sanctuary to a semblance of its original condition.

The most extensive prairies occupy the northern and western portions of the preserve. This observation area is along the trail near the north entrance:

In early June, during our brief stay at our second home in northeastern Illinois I got out to Nelson Lake in hopes of seeing three particular bird species that I missed on my last trip here a few weeks ago. These were Henslow's Sparrow, Sedge Wren and Dickcissel.

The Dickcissels were fairly abundant, so I spent most of my time looking and listening for the endangered Henslow's Sparrows. This bird is extremely selective in choosing nesting areas and its loose colonies must relocate frequently. They require a layer of two or three years' accumulation of dead grass and will not build their nests an area that has been recently burned. The pattern of controlled burns assures a variety of habitats to accomodate the needs of different species. I thought I found one such area where the Henslow's Sparrows might nest, but was obviously wrong (I returned the next morning and heard at least 4 males singing but never caught sight of a single one).

Here are some images of Henslow's Sparrows (Ammodramus henslowii, 5 inches in length) from previous years. They are tiny sprites who put great effort into their songs which come out as little squeaky "s-lip," uttered at intervals of several seconds.

In good light the head of a Henslow's Sparrow appears greenish:

Moving furtively through the grass, it is difficult to keep one in focus.

Several other sparrow species nest in the prairies of Nelson Lake. In size and habits, the Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum, 5 inches) most resembles the Henslow's but is more common. Individuals vary somewhat in plumage, but note its clear breast and lack of malar (mustache) stripe. This individual is brightly colored:

Another Grasshopper Sparrow appears more somber:

Savannah Sparrows are heavily streaked and a bit larger (5 1/2 inches):

Savannahs often sport a central breast spot and a bit of yellow in front of the eye, but these features are not always evident.

The even larger Song Sparrow (6 inches) has a longer tail is the most common sparrow on the prairie.

Field Sparrows (5 3/4 inches) breed in the brushy margins of the grasslands:

Sedge Wrens (4 1/2 inches) are fairly common but also change their breeding locations, as they prefer shorter grass and sedges, usually within sight of water. Actually I did not seek them out this time as I had spent at least two hours searching for Henslow's Sparrows. Sedge Wrens give away their location by their distinctive chattering song. They can be extremely elusive, singling along the trails, loudly but unseen. (I heard several Sedge Wrens the next day and caught sight of one but did not succeed in photographing any. These photos were taken during prior seasons at Nelson Lake).

Typically, their tiny tails are bent forward over their backs.

I missed the Dickcissels earlier because they are very late migrants, usually not arriving at Nelson's Lake until early June. This time I found several males singing on their nesting territories.

This Dickcissel chose a blue silo as a backdrop:

It burst into song:

I accidentally caught this Dickcissel in flight, revealing its stunning bright chestnut wing coverts.

I will be away from Internet and cell phone service for much of these two weeks and prepared several posts in advance, but plan to get back with a "live" report as soon as possible.